This article is published in Aviation Week & Space Technology and is free to read until Aug 08, 2024. If you want to read more articles from this publication, please click the link to subscribe.

IATA director general Willie Walsh opens the 2024 IATA AGM.

If consensus is difficult to achieve on an organization’s key policies, it can help to tweak the messaging.

That appears to have happened in the 12 months between the 79th IATA AGM in Istanbul in June 2023 and the 80th AGM in Dubai this year. On the most important issue—sustainability—the key message remains the same: IATA members are committed to achieving net zero carbon by 2050, the target they set at the AGM in 2021. But at the Istanbul AGM, there were clear signs of friction among members about how to get there and if it was even possible.

It shouldn’t be surprising that there are differences in opinion and confidence levels on sustainability targets. IATA’s membership has grown to 330 airlines based in 120 countries that carry 80% of the world’s air traffic. Government aviation policies, availability of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), investment in sustainable technologies and air travel demand trends vary considerably from country to country.

One of the main points of contention was not the 2050 target—although some did question its feasibility—but rather an interim target that has emerged since 2021 that pushes airlines to use SAF as 5% of their fuel by 2030, a goal that looks frighteningly close when SAF remains extremely hard to find in meaningful, widely available quantities.

That 2030 target, which predominantly came from European governments wanting to make “green” statements, was largely disowned by IATA at an AGM sustainability panel session. When pushed by a moderator on why IATA was backing off from the 2030 target it had previously pushed for, IATA director general Willie Walsh—who was in the audience—strongly rebutted that argument.

“We absolutely did not push for 5% by 2030, and the reason is because we don’t believe the fuel companies can achieve 5% by 2030,” he said. “The governments pushed for 5%.”

Walsh added, “I think that governments have a responsibility to assist in the targets that they have set.”

Qantas chief sustainability officer Andrew Parker, who was on the panel, said big airlines like his were “out of the door” in getting funding to develop SAF but were “nowhere there” when it came to the 2030 interim targets. SAF availability was critical for airlines like Australia-based Qantas. “We don’t have a train to Singapore, so we need SAF,” he said.

Qantas is working with multiple partners to increase the SAF supply and make it more affordable, but Parker admitted it was “like having heart surgery while running a marathon. I think by 2030 we will be short of [SAF] supply, and you cannot digest it being four times the cost of jet [fuel]. We have to build scale; we have to think about producing billions of liters of SAF, not millions.”

POLICY CHANGE

That question of SAF production scale and cost, along with the environmental mandates, fees and taxes that some airlines face, also helps explain why IATA airlines want to be clear on what they can support and what they cannot.

The association wants governments to focus on policy measures that can boost SAF production. These include diversifying feedstocks beyond the HEFA feedstocks that currently dominate to those such as agricultural and forestry residues and municipal waste; making it possible to co-process SAF alongside crude oil to boost production; putting in place incentives to shift the output balance away from diesel for road transportation in favor of SAF at renewable fuel facilities; and putting in place incentives to boost investments in renewable fuel production.

“Incentives to build more renewable energy facilities, strengthen the feedstock supply chain, and to allocate a greater portion of renewable fuel output to aviation would help decarbonize aviation,” Walsh said. “Governments can also facilitate technical solutions with accelerated approvals for diverse feedstocks and production methodologies as well as co-processing renewable feedstocks in crude oil plants. No one policy or strategy will get us to the needed levels. But by using a combination of all potential policy measures, producing sufficient quantities of SAF is absolutely possible.”

Accounting for and monitoring SAF production and uptake is also important, and IATA said it would establish a SAF registry, supported so far by 17 airlines, one airline group, six national authorities, three OEMs and one fuel producer, that is scheduled to launch in the first quarter of 2025.

Three weeks after the AGM closed, Lufthansa announced it would introduce an environmental cost surcharge on some of its fares to help offset the growing costs of complying with European environmental rules, saying it would not be able to bear those extra costs on its own.

The surcharge will apply on flights departing European Union (EU) countries as well as the UK, Norway and Switzerland, and comes into force from Jan. 1 on all tickets issued from June 26 onwards for all flights sold and operated by Lufthansa Group airlines.

Europe’s airlines argue that the EU SAF mandate set to come into force from Jan. 1 put them at a disadvantage against carriers in other regions—in particular the US, with its incentive-based scheme to help boost SAF volumes. Similarly, Air France-KLM has introduced a SAF ticket surcharge. The question remains whether other airlines will follow suit or try to play the cheaper fares card.

In an AGM media briefing, Walsh was clear that the additional costs related to meeting the airline industry’s decarbonization goals would lead to higher ticket prices. He said that while airlines work “extremely hard” not to raise ticket prices, the extra costs cannot be ignored.

“Ultimately, ticket prices may well increase,” he said.

For airlines, the shift in government aviation sustainability policies has added to the challenge. ICAO led the way for aviation and all industries when its member states agreed to the carbon offsetting and reduction scheme for international aviation (CORSIA) agreement in 2016. CORSIA was the first global market-based measure for any industry sector and was aimed at replacing a patchwork of national and regional regulatory initiatives and minimizing market distortion.

But CORSIA is barely mentioned these days—with this AGM being no exception. Government aviation policies have shifted from carbon offsetting to carbon reduction. IATA’s Fly New Zero 2050 commitment was meant to address that shift, but then the goal posts moved again with the 2030 “interim” targets and mandates set by lawmakers regardless of whether the mechanisms were in place to meet them.

That seemed to be what IATA leadership wanted to counter at the Dubai AGM and why it was important to send a unified message on what they can agree on versus public bickering over what they cannot.

Another subtle shift in sustainability messaging at the Dubai AGM was that airlines are no longer going to lay down and give up on the right to grow. Since 2019, EU and European state governments have mostly promoted the idea that airlines don’t need to fly as much and that it’s okay—even desirable—for people to fly less or take alternative transportation modes, such as trains. IATA has been publicly reticent to push back against that idea, probably for fear of retribution from regulators or environmental groups.

But that has split the IATA community.

Understandably, airlines in emerging, fast-growing regions like Africa, India and South America are becoming more vocal about how their growth is good for humanity, local economies and trade, which ultimately provides the wealth and wherewithal to invest in sustainability initiatives.

Not surprisingly, therefore, the 81st AGM in June 2025 will be held in Delhi and hosted by Indian LCC IndiGo, whose CEO, Pieter Elbers, is the former CEO at KLM and has been inducted as chair of the IATA board of governors.

Addressing a question from ATW at the end of the AGM, Elbers said, “It’s been 42 years since the AGM was staged in India and the world has changed—certainly, India has changed. It is now the largest market in the world.

“India has an ambitious agenda on new energy knowledge and expertise. What does aviation bring? It brings the freedom to travel; it’s a force for good. The opportunities and the benefits are very visible in India.”

Walsh also made the point that India was making a transition to wind and solar power and that the aviation industry’s path to 2050 was not a straight line: “It’s going to be exponential progress, not linear. We are not going to promise something that we don’t believe is achievable. Five percent by 2030 is very difficult, but we are committed to zero by 2050, and we are determined to get there.

“Passengers should have heard from member airlines how we strive each and every day to provide service and their very strong commitment on our journey to net zero, which is an ongoing and united endeavor.”

OTHER INITIATIVES

If sustainability and 2050 was the strongest point of consensus, there were other issues where it seemed the board of governors had decided that presenting a united front was the better way. Government policies were again the main target.

In his opening remarks, Walsh warned airlines must stay vigilant about governments “going rogue” on globally agreed aviation standards, as the Dutch government did when it moved to cut Amsterdam Schiphol Airport’s (AMS) capacity without consultation. Walsh said this had been “a major afront to global standards in the Netherlands.”

The Dutch government wanted to permanently cut AMS’ capacity by at least 40,000 flights annually without consultation to address what it said were noise concerns in communities around the global hub airport.

Airport noise standards are embodied in ICAO’s balanced approach agreement that was signed in 2001 and is enshrined in the Chicago Convention and supported in law in the EU and other regions.

“The Dutch paid no heed to it in their politically motivated effort to cut Schiphol’s slots, without consultation. And they had no concern for the Worldwide Airport Slot Guidelines—a global standard that was never intended to accommodate such a retrograde and illegal action,” Walsh said. “We protested. And when the EU and US joined, the Dutch backed down. It was clear that allowing the Dutch to ‘go rogue’ on global standards had the potential to create a retaliatory mess. We cannot let governments forget that critical fact. We must remain vigilant. The Schiphol file is not totally closed. And the Belgians appear to be trying something similar.”

Walsh highlighted a number of other challenges that the airline industry was confronting on a united front—many of which add significant costs—while operating on “wafer thin” margins.

Airlines collectively are expected to post record revenues of almost $1 trillion this year, IATA economists estimate, but to generate a net profit of only $30.5 billion, representing a tiny net margin of 3.1%.

“Governments who love to look to our industry for new tax revenues need to understand that our margins are wafer thin and we rarely earn our cost of capital,” Walsh said. “This year, airlines in aggregate will earn a 5.7% return on invested capital, and that is well below the average 9% cost of capital.”

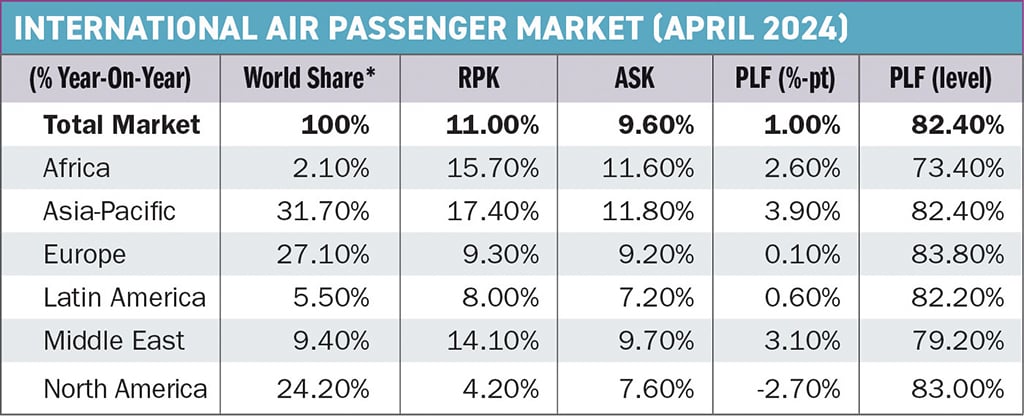

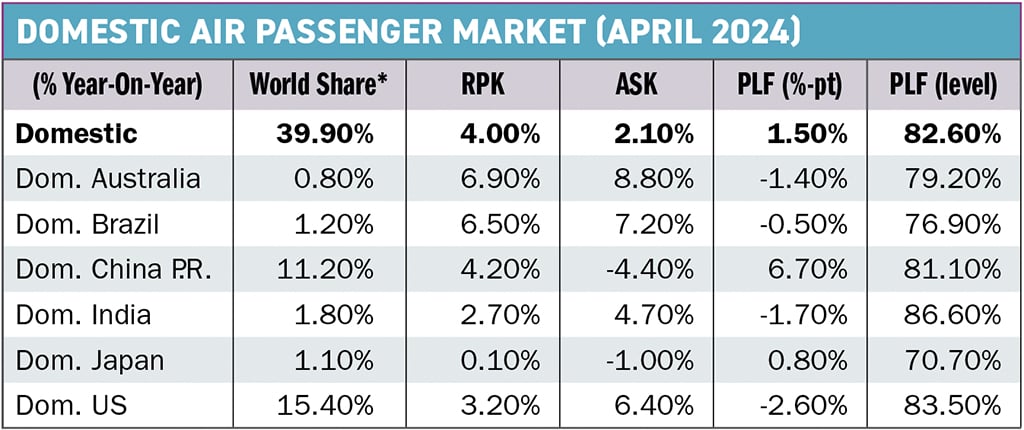

Demand for air travel will grow by 11.9%, much faster than the average 3.8% IATA expects for the coming years. All regions are up significantly, but the growth is driven by the ongoing recovery in Asia-Pacific (17.9%) and Europe (11.1%).

Still, IATA sees a substantial shortfall of aircraft deliveries for 2024. The association believes that 1,583 aircraft will be delivered by manufacturers this year, 11% less than forecast only six months earlier. The shortage of aircraft is partly compensated for by the deployment of larger units where possible and by delayed retirements.

IATA chief economist and head of sustainability Marie Owens Thomsen pointed to underlying trends that could support airline growth in the future. The growth of the world economy is largely driven by services and “services drive longer business cycle expansion, which is good for everyone,” Owens Thomsen said, because it can make economic downturns shorter. “It is more important to avoid a recession than to maximize growth.”

Owens Thomsen said the forecast 3.2% increase in global GDP provides the airlines with an unusual level of stability which “is good for everyone.” Airlines benefit from low unemployment but are also impacted by high wage increases that typically come hand-in-hand with a full jobs market.

If that forecast holds true, the world’s economies could give airlines a more stable environment in which to continue their recovery from the blistering financial and operational impacts of the pandemic. As they maneuver through that recovery and the sustainability imperatives, it will help to have a clear message on what makes sense and what doesn’t.